At work in the forest

Managing the large forest areas of Fiskars ironworks required several employees. The employees were divided into different classes based on their education and job tasks, with the highest being the forest managers who made decisions on different matters, and forest technicians assisting them in the office. In the 1800s, Fiskars employed a forest ranger whose duties partly resembled those of a forest technician. The forest ranger took care of their area, allocated tasks, and participated in game management.

The forest workers were responsible for the actual logging, transporting the trees, burning charcoal, and other practical tasks. Over the centuries, they included peasants, tenants, ironworks forest workers, and numerous seasonal workers, such as those involved in floating. Forest workers have been referred to as forest laborers, lumberjacks, and later, loggers.

Before the invention of the chainsaw and other machinery, forestry work was strenuous. Forestry work was mainly conducted in winter when it was cold and there was a lot of snow. Rural populations engaged in forestry work as their primary livelihood or as supplemental income. The landless rural population primarily carried out logging work. By the late 1940s, there were over 300,000 people employed in forestry work in Finland.

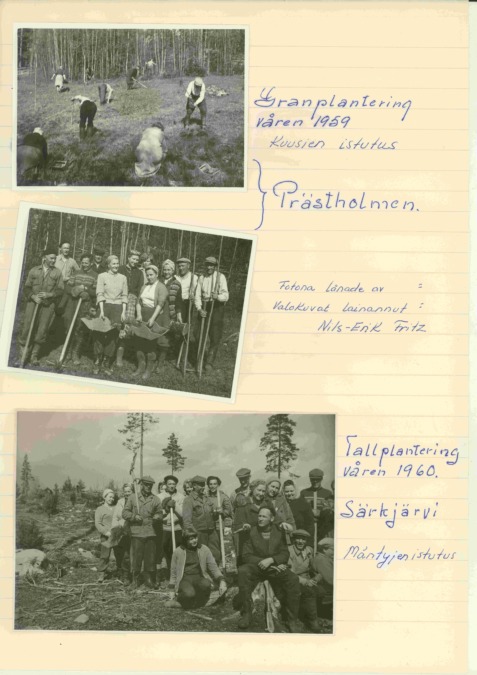

Pictures from the photo album of forest technician Nils-Erik Fritz. Photo: Fiskars Museum Image Collection.

Forest workers

A charcoal mound is a pit where hardwood is burned with an uneven flame to turn it into charcoal. The mounds were prepared and burned in the autumn or winter, fitting into the agricultural calendar when the growing season was not underway. Peasants transported the charcoal over difficult journeys to the Fiskars ironworks. In exchange for the charcoal, they received charcoal tokens (a kind of token) indicating how many barrels one charcoal token equated to. With these tokens, peasants could buy products such as salt and spirits from the ironworks store. Charcoal tokens could be exchanged for real currency. They were in use from the 1700s until around the beginning of the 1900s.

In addition to the factories, most of the housing in the ironworks was also heated with wood, so a lot of firewood had to be reserved from the forests of Fiskars for the winter. There were large stacks of firewood in the 1800s both within and outside of the Fiskars ironworks. The ironworks employed permanent forest workers, and additionally, there was temporary labor coming from elsewhere during peak seasons. Workers were needed not only for cutting down and transporting trees but also for tasks such as tree planting and clearing sapling areas.

A Forest Worker’s Everyday Life

(from the book “Dönsby” by Ann-Marie Lindqvist)

Henry Lindqvist (born in 1917) from Dönsby, Karjaa, recounts what it was like to work in the forest in the 1930s.

“It was a cold, gray winter morning. The year was 1934. Shivering, he went to the stable to feed the horses. Both the horses and the workers had a tough day ahead. Mother Hilda had fried potatoes and bacon and packed food for Henry and Hugo for the week. They set out at seven in the morning. In addition to the two of them, the group included Uno and Gösta from Böle.

Forest workers transported firewood and props from the forests of Fiskars. A group of four lived in a room about 4×4 meters in size. The room had a stove and bunk beds – it was very basic. After a day’s work, they dried their clothes and harnesses. The work in the forest was tough. The firewood or props had to be transported to a flat area, from where they were and then loaded onto a log sled, five stacks at a time. The firewood was driven about five kilometers to the households of Fiskars. They managed to make two trips a day. If the hill was too steep, another horse was used to help pull the load. The horse and the worker knew each other well. When the horse was commanded to pull, it did its best.

In the mornings, Henry’s task was to fry or cook porridge and pour coffee into a bottle, which was wrapped in newspaper and kept in a wool sock. Throughout the day, they ate sandwiches and drank coffee. In the evenings, potatoes were boiled, and bacon was fried. When the workweek ended, it was nice to come home, eat good food, and sleep in a comfortable and soft bed. Forest work was the way to make a living at that time, and this money had to last until the next season. There were not many other job opportunities available.”

Coffee-Hilda

Hilda Sjöholm worked as the housekeeper for forest manager Arvid Lindberg. Additionally, she ran a café in her apartment in an old barracks in the early 1900s. The apartment was divided by a curtain into two parts. One part was Hilda’s own space, and the other part contained the kitchen and café, where she served food and coffee. Forest workers and forestry supervisors without their own families would visit the café. Hilda baked bread herself, and a cup of coffee at Hilda’s café cost one mark. Hilda’s place could get crowded; at its busiest, there were 10-20 forest workers there simultaneously, and almost everyone had to stand.

“Coffee-Hilda”, Hilda Sjöholm. Photo: Fiskars Museum Image Collection.

Log floating

Logs were floated from the forests north of Fiskars through Antskog and Fiskars ironworks to the ports of Pohjankuru. The water in the rivers was dammed to conserve it for the log driving season. In the 1940s, near Fiskars, 10-year-old boys participated in log driving as traffic controllers. Their task was to shout upstream if the logs became congested, so that no more logs would be released into the sluice until the congestion was cleared. Older workers were stationed upstream at the upper end of the sluice. There were sluices at power plants and, for example, at the Fiskars mill. Adults were paid 40 marks per hour for log driving, while boys received half the wage of adults. Children who participated in log driving were excused from school during the log driving season. Log driving was discontinued in 1961, and trees began to be transported by trucks.

Voluntary work during the war years

During the war years from 1939 to 1944, there was a shortage of coal and oil, so heating had to rely on firewood and forced logging. Because there was a shortage of workers, everyone capable was called upon to participate in voluntary work gatherings. The aim was for each person to produce a “motti” (1 cubic meter) of firewood. At the same time, the home front was involved in a collective effort for the homeland.

Forest ranger

As the name suggests, a forest ranger (or guard) was responsible for overseeing their designated forest area. The duties of a forest ranger included tasks such as allocating forest work, monitoring tree growth, preventing poaching, and wildlife management. The specific responsibilities have varied over different time periods. Forest rangers participated in hunting and gamekeeping activities. Forest rangers have lived in various places, including the worker houses in Peltorivi.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, David Johan Kinnunen served as a forest ranger for Fiskars. He was married to Alexandra Wilhelmina Blomberg, and the family had three sons.

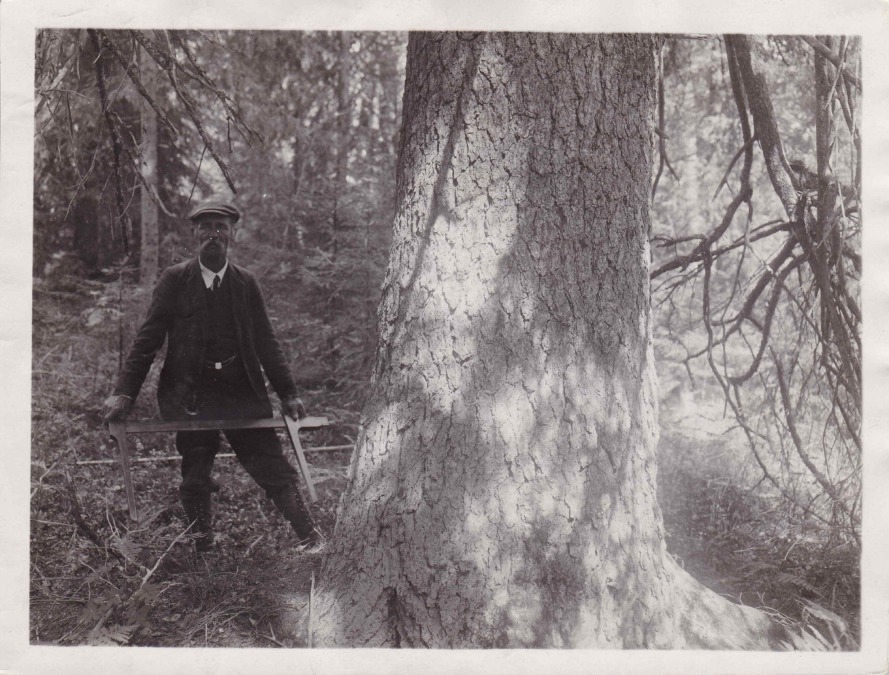

Forest ranger David Kinnunen measuring a large spruce tree in the year 1922. Photo: Fiskars Museum Image Collection.

Forest Technicians

A forest technician was an employee of Fiskars ironworks, working at the ironworks office. In the 1950s, Fiskars forest technicians were responsible for planning, forest mapping, accounting, and payroll calculation. Salaries were distributed for a long time in cash directly to the employees.

In the 1970s, payroll administration shifted to the Post Bank, where the forest technician sent the payroll lists. Employees then collected their salaries directly from the bank. In the 1960s, when forest technicians moved to Fiskars, they resided on the third floor of the Stone House, where there were a few rooms for the civil servants working in the ironworks office.

Forestry Managers

The forestry manager’s workplace was the ironworks office. Their job included forest management planning and serving as supervisors. The first forestry managers in the 19th century studied in Sweden, familiarizing themselves with the latest methods of their time. Later, education in forestry was also available in Finland. Organizing hunts, to which distinguished guests were invited, was also part of the forestry manager’s job.

I.A. (Arnold Ingram Arvo) von Julin served as the long-time manager at Fiskars, responsible partly for forestry in addition to the ironworks. Everyone at Fiskars knew I.A. von Julin, and among the ironworkers, he was referred to as “forsmestari” in Finnish, which translates to “forestry manager.”

Forest Managers at Fiskars Ironworks:

J.W. Aspelin, served as a forest manager from 1843 to around 1845

F. Durietz, from 1845 to around 1855

O.W. Danér, from the early 1860s to 1868

C. Meller, during the 1870s

N. Tallgren, from 1876 to 1890

Arvid Lindberg, from 1890 to 1921

I.A. von Julin, in the 1920s

Ernst Lönngren

Erik Roos, approximately from 1945 to 1964

Claes-Johan Grönvall, from 1965 to 1988

Tehdaspuu Oy (consultant Örnmark), from 1989 to 1995

Kåre Pihlström, from 1995 to 2015

Robert Lindholm, from 2015 onwards

Did you know that:

In the early 20th century, the lodging place for temporarily residing forest workers in the ironworks was called a hut (in Finnish “murju”).

During the Continuation War, there were Russian prisoners of war working in agriculture at Fiskars ironworks, who also chopped firewood for elderly ironworkers.

Even in the 1960s, forest technicians paid wages in cash during work in the forests and forest cabins. Carrying a large amount of cash with them in the forest, they also carried a weapon to prevent robbery.

Sources:

Fiskars Museum. Collecte database image and object information.

Pohja Local History Archive. Interview material.

Literature:

Fiskarsin kotiseutuyhdistys. Fiskarsin museon 50-vuotisjuhlajulkaisu. Esineitä kuvin ja sanoin. 1999.

Lindqvist, Ann-Mari. Dönsby. Bondesamhället möter nutid. 2022.

Nikander, Gabriel. Fiskars bruks historia. 1929.

Roiko-Jokela, Heikki (ed.). Ihminen ja metsä 2. Kohtaamisia arjen historiassa. 2012.