Iron Out of Ore

Iron has been produced in Finland from bog ore and limonite since the pre-historic times. Since the late Middle Ages, when Sweden was the leading iron producer in Europe, iron ore was fined into iron in blast furnaces. Both smelting and further processing were concentrated early on to the Western Uusimaa in Finland, where access to mountains, forests and water power was good. Iron products were shipped to Sweden across the Gulf of Bothnia, and little by little also to other Baltic Sea countries.

Sir Erik Flemming, the owner of the Suitia Manor in Siuntio, was the first to begin prehistoric iron production on the Western Uusimaa. Since 1542, iron ore was mined at Ojamo in Lohja. Between 1530 and 1570, ore was probably also mined in Tupala, Siuntio, where the oldest remains of a bloomery in Finland can be found. Later on, Ojamo’s ore was fined in Mustio (since 1560), Ansku (since 1630) and Billnäs (since 1642).

A wealthy merchant from Turku, Jacob Wolle, founded the Ansku Ironworks in 1630. Simultaneously he took over Mustio. When Ojamo’s ore started to run out, and its quality got worse, ore started to be shipped in from Utö, Sweden. Despite tax reductions and land loans, Wolle went bankrupt, and the ironworks went to his German-born creditor, Peter Thorwöste.

In 1649, Thorwöste built, with the help of a privilege granted by Queen Kristina, a wrought iron hammer, a blast furnace and a smithy on the land of the old Gennäs farm beside the Fiskars river. Most of the ore used in Fiskars was shipped from Utö, Sweden, both with their own and rented ships to the Pohjankuru harbour. From there the ore was transported downstream Fiskarsinjoki by barges to the blast furnace. Since the 1670’s, iron ore was also mined in the Malmberg mine in the municipality of Kisko.

Pohjankuru harbour

From Kisko, the ore was transported in the winter by sleighs, across the frozen Seljänalanen, and during open waters, by barges to Ansku. Since the ore had a high quantity of sulphur and copper, it was mixed with the ore brought from Sweden. Iron mining continued at Malmberget until 1866.

When Peter Thorwäste died, he was succeeded by his widow, Elin Såger. The probate left Ansku and Fiskars to their son, Johan Thorwöste, who stayed in charge until his death in 1712.

Smiths and other workers

In the 17th century, the number of workers in Fiskars varied between 14 and 95. Most of the workers were smiths, but the Ironworks also had other workers, such as a sawyer, a tailor and a shoemaker, as well as men who worked at the ore ships. A blast-furnace master also worked at the Ironworks. He was a highly respected person at the Ironworks. He had to be familiar with the jobs of the ore crusher, the stoker (who supplied the furnace with coal, ore and limestone), as well as the job of a workshop hand. Farmers who worked on the land belonging to the Ironworks, were also counted as the ironworks workers. They were freed from the army, and this was compensated to the Ironworks with statute labour. In 1657, farmers did 1,5 statute labour days a week.

Blast-furnace masters in the 17th century:

Jost Dickman (the 1650’s)

Michel Mertel (1669)

Simon Ransk (around 1690)

In the 17th century, most of the workers at the Ironworks came from Sweden. They probably were originally from Wallonia and Germany. Since the Walloon forge had not yet been adapted in the 17th century Finland, the Walloon smiths worked with the blast furnace, coal and the German forge. The workers lived in the Ironworks houses, and they were allowed to use a plot of land, and to keep cows. Their salary was paid in perks.

All conflicts between the workers and the owner were handled at the district court, or special ironworks courts. The Ansku-Fiskars Ironworks even had a provost, a kind of predecessor for ironworks police, who upheld law and order.

The Ironworks after the Great Wrath

In the 18th century, the Fiskars Ironworks was owned by Swedish businessmen, who handled its operations through an inspector. After the Great Northern War in 1700-1721 (a time known in Finland as the Great Wrath), the merchant John Montgomorie bought the Ironworks. He built and improved the ironworks by, for example, adopting the German forge at the Ansku Ironworks. A new blast furnace was built in 1737, and in the same year the Koski Ironworks and the blast furnace in Tenala were incorporated into Fiskars. These new procurements done in Montgomerie’s time finally led to the ironworks’ bankruptcy and subsequent selling to a trading house in 1752.

In the mid-18th century, when the Ironworks was owned by Robert Finlay, copper was found in Orijärvi, Kisko. Copper ore was fined in Kärkelä, where a copper smelter was founded in 1766. Fiskars and Ansku also started to concentrate in refining copper.

In 1780, the production of wrought iron, and finally all the operations, were moved from Ansku to Fiskars. Three years later, during economic difficulties, the ironworks was bought by the merchant Magnus Björkman. Despite the fact that the blast furnace reached a new record in production in 1781-1789, around 450 tons of pig iron, it was closed in favour of refining copper in 1802.

Bengt Magnus Björkman

When Finland was annexed to Russia in 1808-1809, Swedish ironworks owners were required to get Finnish citizenship in order to retain their possessions. They were also required to move to live in Finland. Because of this, Magnus Björkman sold his Finnish possessions to his son Ludvig, who moved to Fiskars in 1815. In Ludvig’s time, the ironworks invested in new buildings, and the construction of, for example, the Ironworks manor, the Kivimuuri, was started. Ludvig was known for his fiery nature, and he was sentenced to prison after killing a worker. When the Ironworks was under Ludvig’s ownership, its functions began to suffer, and in 1822, Fiskars was sold to apothecary Johan Jacob Julin.

Life at the Ironworks in the 18th Century

The Ironworks had been destroyed in the great war, and had to be rebuilt. To do this, blast-furnace master Bengt Bengtson Qvist was tasked with designing Fiskars’s first town plan. In 1765, the construction of the first building in the plan, the foreman’s house, the present-day ironworks office, was started. In addition, workers’ housing was built, including some of the houses on modern Peltorivi.

In the 18th century, Walloon forge was introduced to Antskog, and therefore new habitants with Walloon roots moved to the municipality from Roslagen, Sweden.

Among those who moved to Antskog:

Clas Pira – a smelter

Vilhelm Forss – a smith

Michael Gilliam – a smith

Noe Tillman – the head journeyman

Jean Pouse – a smith’s hand

Jean Dardanell – a smith’s hand

Anders Erman – a smelter’s hand

Bonnevier – a smelter

Giers – a coal boy

Stokers in the 18th Century:

Johan Ransk

Anders Uhr (until 1757)

Lars Uhr

Gabriel Winter

J. Frisk

Erik Nässling

In the 18th century, there were, on average, 44 men working. In the copper smelter, there were a smelter hand, a helper, a slag carrier, two stokers and two crushers. The Smiths’ Association was very particular about how the salary was distributed amongst the workers. The salary’s purchasing power was low in the 18th century, and so, in 1764, Finlay started selling grain at the Ironworks’ own price. Walloon smiths’ perks also included an additional compensation, a so-called vinpeng, and probably a flat and firewood. Older workers could also receive some sort of pension and healthcare was provided in the form of a medic, who handed out simple medicine free of charge. Injuries inflicted at the workplace were compensated.

The importance of a working community was understood as early as the 18th century. Ironworks owners organised Midsummer parties for their workers, where beer, wine and tobacco was offered. The drinks and the relaxed atmosphere were also part of starting barges, bigger jobs and annual inventories.

In the first half of the 18th century, there were only a few clerks and the stoker was the one who worked as the overseer at the Ironworks. Slowly the business started to require more people in administration, and during this time a new profession, the bookkeeper, was introduced. Clerks received most of their salary as perks, but it also included proceedings from, for example, from the inn.

The tenants and farmers on the Ironworks land were also considered as workers. Coal work had to be relearned after the war. Because of this, coal houses were built in the Ironworks’ forests, and a coal watch was hired to look over the coal spots.

From Coal Workshop to a Corporation

Johan Jacob Julin bought the Ironworks, which at the time was called the Fiskars Coal Workshop, in 1822. He immediately began modernising the copper industry. He improved the transportation possibilities from Orijärvi to Fiskars by having the Antskog lock built. Thanks to the lock, ore could be transported all year round. From the mid-19th century, the copper industry had lost its profitability, and so the activities at the Koski copper workshop, the Orijärvi mine and the refining facilities at Kärkelä and Fiskars were slowly brought to an end. Mining at the Ojamo mine stopped in 1873.

Kvarnsjö lake and sluice in Antskog

Since Fiskars was dependent on Finnish ore in Julin’s time, mining was started at Malmberget. This provided raw materials for iron production. Pig iron was produced in the Koski blast furnace, and later also in Trollshovda, whereas the production of wrought iron was concentrated in Fiskars. Julin also founded some production facilities, such as a foundry, a machine workshop and a cutlery workshop.

The “good old boss“ died in 1853. After his death, the ironworks was led by caretakers until his eldest son Emil was able to take over Fiskars, Ansku, Kärkelä and Orijärvi. During the leadership of the caretakers, the production of wrought iron was modernised by building puddling and rolling mills. Even though the production capacity increased, the sales did not improve enough on the domestic or Russian markets. A new direction was adopted at the mechanic workshop, and the production of farming tools was started.

On the latter half of the 19th century, economic difficulties and bad harvests almost drove the company to bankruptcy. In 1883, the Fiskars Corporation was established, with Emil, and Johan’s second son Albert, as the biggest shareholders. Albert also became the first president for the company. The Åminnefors, Billnäs and Inha Ironworks were later incorporated into the company. Newer corporate acquisitions include brands such as Gerber, Iittala, Arabia, Hackman, Leborgne and Royal Copenhage Owners of the Fiskars Ironworks:

Owners of the Ironworks

1649-1659 Peter Thorwöste

1659-1669 Elin Såger, Peter’s widow

1669-1712 Johan Thorwöste

1712-1731 Johannes Thorwöste

1731-1752 John Montgomerie

1752-1755 Charles & William Tottie

1755-1778 John Jennings & Robert Finlay

1778-1783 Jean & Carl Hasselgren

1783-1815 Bengt Magnus Björkman

1815-1822 Bengt Ludvig Björkman

1822-1853 Johan Jakob Julin, von Julin from 1849

1853-1866 3 caretakers

1866-1875 Emil Lindsay von Julin

1875-1883 board of directors

1883-1984 Fiskars Aktiebolag – Fiskars Corporation

1984-1998 Fiskars Oy Ab

1998- Fiskars Oyj Ab

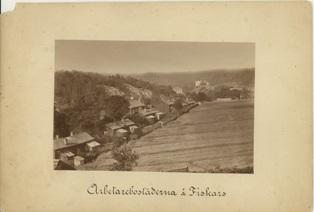

The Bell Tower House and Barracks

The Ironworks got its outward appearance in Johan Jacob von Julin’s time. To help with the planning, Julin used Finland’s top architects of the time, such as C.L. Engel, J.E. Wiik, A.F. Granstedt, W. Aspelin and Charles Bassi. Among the first buildings were the old barracks. Workers and clerks lived in the barracks together. Soon the clerks were built separate houses, such as Rosehill and Fagerbo. For the workers, Kardusen was built next to the marketplace, and Tabor and Stenkulla at the Upper Ironworks. In addition, a school and later also a stable were built, and connected to each other with a bell tower. The building was later called the bell tower house. At the end of the 19th century, several bigger barracks were built for the workers a little farther from the industrial facilities.

Sources and literature

Anttila, Upi. Ferroso. 2001

Fager, Paul. Fiskars bruks historia. 1899.

Carlson, C. E. Fiskars 350. 1999.

Korhonen, Mikael. Vallonsmeder och krigsbarn. 1995.

Matvejew, Irina. Fiskars vår hembygd. 1949.

Nikander, Gabriel. Fiskars bruks historia.

Suoja, Kauko. Vitikkalan suvun juuria, Thorwösten suku

Turunen, Mirja (toim.). Ruukkien retki. 1998.

Särkkä, T. J. Fiskars, trehundra år av järnförädling och industrikultur i Finland. 1935.

Wadsted, Bengt. Utlåtande angående magnetisk och geologisk undersökning för Aktiebolaget Fiskars – Juli 1942.

Internet:

Muinaisjäännösrekisteri

http://kulttuuriymparisto.nba.fi/netsovellus/rekisteriportaali/mjreki/read/asp/r_default.aspx

http://www.vallon.se/wiki/index.php?title=Yrken

http://www.vallonia-finland.com/valloniajasuomi.htm