Fiskars ironworks was not suitable for modern industrial manufacturing. The last factories to be built were the scissor factory and the assembly hall for tractor ploughs. Today these buildings are known as the flagpole factory and the knife factory. These names come from the last industrial activity that took place in the buildings. Today the flagpole factory houses a glassblower, and the knife factory houses a brewery and distillery. Modern factories and buildings did not suit the environment of the old ironworks, but The Finnish Heritage agency allowed the knife factory to be built as it allowed industrial manufacturing to continue in the ironworks. The older buildings were culturally and historically valuable, and could not be torn down to make way for modern industrial facilities. Thus it was simpler to build new factories elsewhere.

In 1983, the property company Pohjan Ruukkiteollisuus was founded with the purpose of preserving the cultural and historical environment of Fiskars and Billnäs ironworks, where the buildings were now empty and abandoned. The property company owned by the Pohja municipality received a subsidy from the state, allowing it to purchase several properties in both Fiskars and Billnäs in 1984. By this time, most factories in Fiskars had already moved elsewhere.

The earlier mentioned scissor factory almost immediately became too small, as Fiskars had underestimated the popularity of its orange-handled scissors. The 800 m2 industrial hall could not meet the demand of the scissors, and later the building was used for manufacturing flagpoles. The assembly hall for tractor ploughs, completed in 1974, also shows how quickly business could fluctuate. In the 1980s plough manufacturing became unprofitable, and instead the building was used for making knives and cutlery. This gives the building its current name, the knife factory. Industrial manufacturing in Fiskars came to an end in 2001, when the production of knives was moved to Billnäs, where both scissors and knives were made.

The Cutlery Mill, the Knife Factory and the Copper Smithy – which is which?

The current names of the buildings can be confusing, as some of them come from their original purpose and use, while other names refer to the industrial activity that last took place in the buildings. The buildings in Fiskars have been home to different types of industrial manufacturing for many centuries. Today the Fiskars corporation uses the buildings for other purposes, and therefore new names have been given to the buildings.

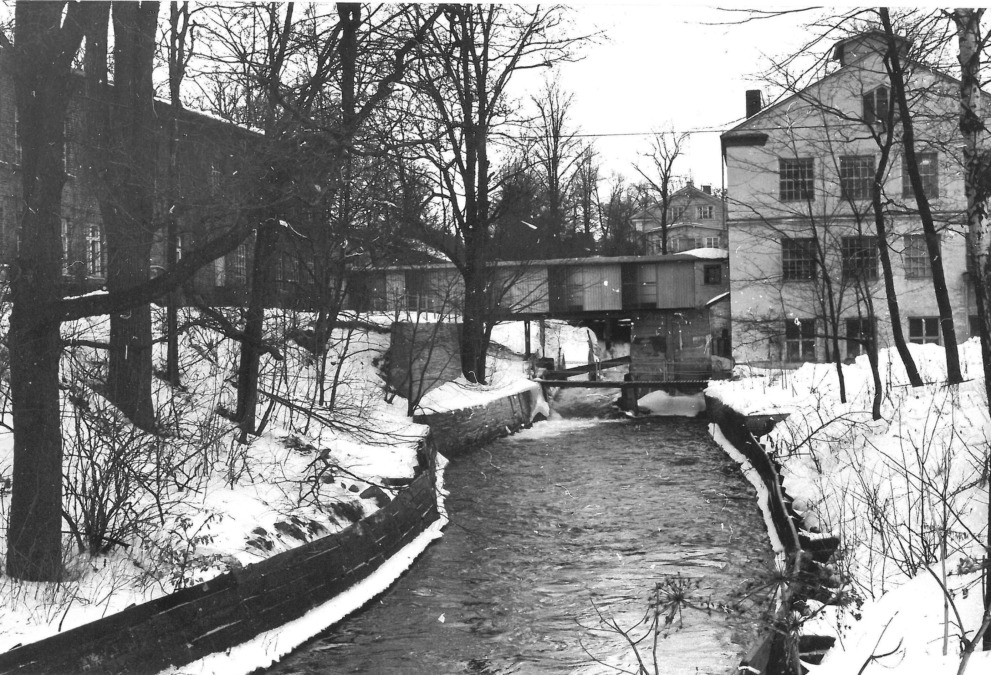

The Cutlery Mill began its production in the 1830s, in a building designed by Carl Ludvig Engel. The building was destroyed in a fire, and a new brick building was built in the same place. Close to the Cutlery Mill was also a copper foundry. This was one of the few buildings that already existed when Johan Jacob von Julin bought Fiskars ironworks in 1822. After some time copper production ended, and products such as cutlery, knives and scissors became more prevalent, and their production expanded to the copper foundry. The foundry was renamed the Cutlery Mill. With the orange-handled scissors more space for manufacturing was needed, as new production methods and machines came into use. A new scissor factory was built next to the Cutlery Mill, but the facility grew too small almost immediately as the scissors turned out to be much more popular than expected. Later the scissor factory was used for manufacturing flagpoles, and thus it is now called the flagpole factory.

For a long time, the horse-drawn plough was Fiskars’ most well known product, as agriculture was a large sector in Finland. To keep up with the technical developments of the times, Fiskars began manufacturing tractor ploughs, which required new production facilities. In 1974 a new building for assembling the tractor ploughs was built on the road called Peltorivi. Fiskars had received permission to build a modern factory from the Finnish Heritage Agency, as it allowed industrial manufacturing to continue in the ironworks. Ten years later, the production of tractor ploughs became unprofitable and manufacturing ended. Afterwards knife production was moved to this building from the Cutlery Mill, and it was renamed the knife factory. Small-scale knife manufacturing took place here until 2001, when production was moved to nearby Billnäs.

The Pohja municipality purchased the Fiskars Cutlery Mill (the Copper Smithy) as part of the real estate deal to buy properties in the ironworks. The building was renovated and a new era began in the ironworks, as the buildings were no longer used for industrial manufacturing like they had been for the last 170 years. The Pohja municipality held art exhibitions in the building, and in the 1980s it was called the Cutlery Mill. So when was the building called the Copper Smithy? After the last Expohja art exhibition in 1989, the Fiskars corporation repurchased the building. It was renamed the Copper Smithy, referring to what it was originally built for. The Fiskars corporation also owned a brick building, also called the Cutlery Mill. In order to tell the buildings apart, the former exhibition space was renamed the Copper Smithy.

As things began to change in the ironworks and industrial manufacturing moved elsewhere, new names were needed for the buildings. The name “the Cutlery Mill” couldn’t be given to three different buildings, so they were called the Cutlery Mill, the Copper Smithy and the flagpole factory. It might have been logical to name the buildings after their original purpose. Then the Cutlery Mill and the Copper Smithy would have kept their names, but the flagpole factory would have been called the scissor factory and the knife factory would have been called the plough factory. But then what would the old plough factory where the horse drawn ploughs were made have been called? Perhaps the current system of naming the buildings is best after all. These names can however cause confusion even among those who are familiar with the history of Fiskars.

Workers’ houses

In Fiskars there are many buildings that for a long time have been used as housing for the ironworks’ workers. The iconic workers’ tenements along Bruksgatan street and the houses along Åkerraden street, which leads up to the museum, were both built during Johan Jacob von Julin’s time. Later in the 19th century larger housing complexes were built in the areas Kulla and Hasselbacken. All of these workers’ houses were during the latter half of the 20th century pretty modest, and didn’t fulfil the requirements that modern people set on their housing.

The three houses in Kulla were built in the 1850s, and they consisted of varying numbers of apartments depending on the apartments’ size. One of the houses was renovated in 1950 to make it liveable for retirees. Cold running water was added to the building and a few shared indoor toilets were installed in the hall. One of the other houses never got renovated and water was carried into the house by the occupants until the very end. Many elderly moved away from the house during the 1960s because of its poor condition. The last Kulla house was mostly inhabited by families, and the apartments in this house consisted of two rooms. They made complete renovations there between 1957-1958, and the occupants received cold running water. There were, in other words, never warm running water in these apartments while workers were living in them. It’s often said that back in the day up to 150 children were living in the 50 apartments. The number of children were reduced as the living standards were rising and the families with children, if the possibility arose, moved to the apartments in Hasselbacken, which were larger. The retirees and temporarily employed bachelors were among the last who lived in Kulla.

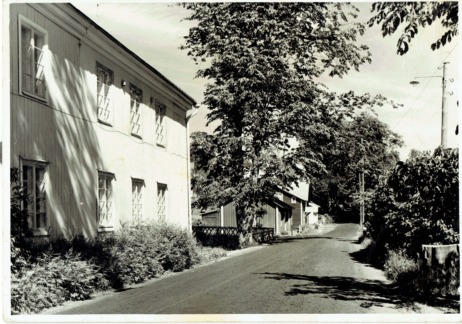

The houses along Åkerraden street were built during the 1820s and the 1830s, where there earlier had been workers’ housing. The name Åkerraden, which translated means Field Row, is derived from the fields that the occupants received so that they could grow some food for their own use. Just as with many of the other apartments in the ironworks, these also became outdated during the middle and latter half of the 20th century. When the municipality of Pohja formed the real estate company ”Pohjan ruukkiasunnot kiinteistöyhtiö”, to prevent the disrepair of real estates, the houses on Åkerraden were among the housing which were sold to Pohja’s real estate company by the Fiskars company. During the 1990s the buildings were renovated and transformed into municipality owned rental housing, and in 2008 they were handed over to the businessman Olli Muurainen, as he bought the real estate that was owned by Pohjan ruukkiasunnot kiinteistöyhtiö. His main goal was to buy the old industrial estates in Billnäs’ ironworks, but the apartments along Åkerraden were included in the deal.

During the 1980s there was a discussion on the issue of apartments for retirees in Fiskars in the local press. The majority of the remaining Fiskars villagers had reached retirement age, adn wanted to continue living in their place of birth. There was a big need for new housing, because the majority of the apartments in Fiskars didn’t reach the expected levels of comforts. The municipality initially wanted to build the apartments for the retirees in the neighbouring village Bollstad, but the stubborn retirees of Fiskars succeeded in expressing the need for apartments in Fiskars, where there still were some services left. The apartments were built on Skomakarbacken street in 1982.

When Pohjan ruukkiasunnot kiinteistöyhtiö bought a large part of the apartments in Fiskars and Billnäs, they immediately began renovations, as the apartments lacked modern comforts. When the housing complexes in Hasselbacken were being renovated an accident happened, and one of the houses burned to the ground just as the renovations were coming to a close. The company then decided to build a new house in the same place, but because the blueprints to the new house were so completely different from the other houses in the area, the plans caused discontent among the ironworkers and the plans were never realised. Another unpopular decision was to close down the public sauna and the public laundry, which were located in the upper Ironworks next to Degersjö lake. The sauna was almost a necessity since most houses lacked modern comforts. The homes that had running water couldn’t accommodate modern washing machines, because the water pressure in the hoses were too weak, and because of this the public laundry was an absolute necessity. Despite protests the decision was implemented and the villagers had to start tending to their hygiene in other ways.